[ad_1]

Understanding the Estate Tax and How It Works

The estate tax tends to get a lot of press – especially in an election year. Some folks call it the “death tax.”

But it’s a tax that impacts a very, very small segment of the population.

That doesn’t mean you can forget about it completely. It’s smart to look at it when you’re planning the rest of your estate. Even if you’re never on the hook for the federal estate tax, you might need to pay them to the state.

Here’s what you need to know.

What is the estate tax?

When someone passes away, the federal and some state governments impose an estate tax on the value of their estate, i.e., all the real estate, insurance, stock, business interests, cash, and other assets the deceased person owned at the time of their death.

Only the wealthy pay the federal estate tax because in 2020, it only impacts estates valued at more than $11.58 million per person ($23.16 million per married couple).

Those threshold amounts are known as the federal estate tax exemption, and they change from year to year. Twenty years ago, the exemption was a comparatively modest $675,000 per person, or $1,350,000 per married couple. But in 2010, the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act increased the exemption to $5 million per person, and gradually increased along with inflation for several years. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 gave it another boost, doubling the exemption from $5,490,000 to $11,180,000 per person in 2018.

So how does the estate tax work?

When someone passes away with an estate worth more than the exemption amount, their executor is required to file a federal estate tax return within nine months of their death. This tax return reports the value of all assets owned by the estate and takes a deduction for any transfers to a surviving spouse or minor child, any debts, funeral expenses, legal and administrative fees, charitable bequests, and estate taxes paid to states. After those deductions, the remaining value of the estate, minus the exemption amount, is considered the taxable estate and is taxed at the top estate tax rate of 40%.

Federal estate tax vs. state estate tax

The federal estate tax impacts less than one percent of estates in the U.S., but don’t breathe a sigh of relief just yet. Each state can impose its own estate or inheritance tax – and the exemption is much lower in some of them.

That brings up a new question: What is the difference between an estate tax and an inheritance tax? The main difference comes down to who pays the tax.

- An estate tax is charged against the estate, regardless of who inherits what. The executor of the estate files one estate tax return and pays the tax out of the estate’s funds before distributing any assets to beneficiaries.

- In states with an inheritance tax, the beneficiary (i.e., the person who inherits money or property from the deceased person) pays the tax. Each recipient is responsible for calculating and paying their own tax.

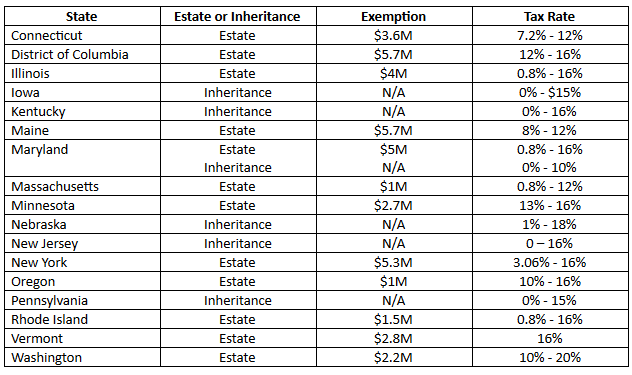

Sixteen states plus the District of Columbia have an estate or inheritance tax, and one state has both. Here’s a breakdown of the states, the type of tax each levy, and the exemptions and rates that apply.

All six states with an inheritance tax allow an exemption for transfers to spouses, and some allow full or partial exemptions for immediate relatives.

How to save on the estate tax

Some wealthy individuals and families have teams of lawyers and accountants to help them avoid estate and inheritance taxes so they can pass on large portions of their estates tax-free. There are several completely legitimate ways to reduce the size of your estate and lower your estate tax exposure.

Here’s an overview of some of those strategies.

Grantor retained annuity trusts (GRATs)

Estate owners put assets with the potential to increase in value into a trust, but the owner retains the right to receive an annuity over the trust’s term – typically two to five years. At the end of the term, the assets are distributed to the beneficiaries – usually the grantor’s children. If the asset (typically stock) increases in value, the gain goes to the heirs, tax-free. If not, the value still goes back to the estate.

Establish a family limited partnership

If a big chunk of your net worth involves a family-owned business or rental properties, you can set up a family limited partnership and make your children or other heirs limited partners. As the general partner, you retain control of all business decisions. But any limited partners you bring in will have a financial stake in the company, so the size of your estate will be smaller.

Gifts

Another strategy wealthy people employ is to gift portions of their wealth to family members. The IRS allows individuals to gift up to $15,000 per person per year without having to file a gift tax return. A married couple can give $15,000 per spouse, for a total of $30,000 per gift. The annual exclusion is per recipient, so a couple could give $30,000 to their adult daughter, $30,000 to her spouse, $30,000 to each of their three children, and so on all in the same year without having to file a gift tax return. The person receiving the gift generally doesn’t need to report the gift as income, either. There’s no limit to the number of gifts you can give each year, so the annual gift exclusion allows people to gradually pass on their assets to loved ones until the value of their estate is less than the exemption amount.

If you make gifts over the annual exemption limit, you won’t necessarily have to pay taxes on those gifts. But you do have to report them to the IRS on a gift tax return, and those gifts count toward your lifetime exemption limit. For example, if you gifted $3,000,000 to your daughter in 2019, then you no longer have $5.79 million worth of exemption – you have $2.79 million worth.

Qualified personal residence trust (QPRT)

If a home or vacation property is a substantial part of your net worth, a QPRT removes the home from your estate for a period of time – usually 10 to 15 years. You continue to live there during this time. When the trust term is up, ownership of the home transfers to your beneficiaries. If you wish to stay there longer, you can make arrangements to pay rent. However, if you pass away before the trust term ends, the home will still be included in the value of your estate.

Irrevocable life insurance trust.

Many people purchase life insurance to protect family members after they pass away. Life insurance proceeds typically aren’t taxable, but they can be included in the value of your estate and push you over the estate tax exemption amount. To avoid this outcome, you can create an irrevocable life insurance trust (ILIT). With an ILIT, the trust owns the insurance policy, not you, so it’s not included in your estate. Keep in mind that if you pass away within three years of transferring a policy to an ILIT, the insurance proceeds will still be considered part of your estate.

Charitable remainder trust (CRT)

With a CRT, you can transfer stock or other appreciating assets to an irrevocable trust. This removes the asset from your estate and gives you an immediate tax break for the charitable contribution. Throughout your lifetime, you receive income from the trust. When you pass away, the remaining trust assets go to the charity of your choice.

These are just a few of the options available to people interested in shielding their assets from the estate tax, and the best options for you will depend on your unique financial circumstances. Be sure to talk to an estate planning attorney or financial planner for help in determining the best way to save on estate taxes.

Other things to know about estate taxes

If you have an estate plan in place but haven’t looked at it in a while, it might be time to give it another look. Some estate planning strategies that made sense a few years ago aren’t as solid in light of recent tax reform.

Estate planning is never a “set it and forget it” activity. As your family and finances change or laws change, strategies for reducing your estate tax exposure change as well. It’s a good idea to dust off your plans and review them with your attorney or tax advisors every few years to make sure they still make sense.

Understanding Estate Tax and How it Works is a post from: I Will Teach You To Be Rich.

[ad_2]